”When I was 11 in Syria, my grandfather used to take me to a small piece of land that my family owned where we used to spend hours together watering the plants and talking about life. This is my only happy place.“[1] (Semaan Khawam)

”For me, home is a safe environment in which to create; it is wherever I can find a peaceful corner in which to do my art. But home is also the place which I can contribute my art to.“[2] (Kevork Mourad)

Our identity is inevitably linked with questions regarding our origins, our roots. Even though we can cover distances around the world in just a few hours or days, stay connected with innumerable people and get in touch with them in just a blink of an eye while our place of birth may perhaps be a thousand miles away – when someone asks us “Where are you from?“ we are immediately catapulted back to the place and the people of our childhood.

Kevork Mourad (*1970) was born in Qamischli in North-East Syria. He‘s got Armenian roots, just like many Syrians whose ancestors came to Syria from the Ottoman Empire, today Turkey, between 1915 and 1945. Mourad grew up in Aleppo in humble circumstances and decided, encouraged by his classmates and teachers, to become an artist at the young age of 6. When he was 14 years old he sold first drawings to a local print shop and saved up the money. His goal was to enroll at the University of Arts in Yerevan, Armenia – against his parents‘ will. He was accepted, studied painting and illustration and completed his studies with a master‘s degree. Today he lives and works in New York and often recalls his childhood days in Aleppo: “The city of Aleppo was a walking museum. The old traditional houses and alleyways, the ironwork and woodwork, the stone carvings and blue and white porcelain, colorful dyed wool on the rooftops… these all fed my eyes on a daily basis. On top of all this, I grew up with Armenian iconography in the Armenian churches.“[3] The impressions of the once so lively city, declared World Heritage Site in 1986 and meanwhile largely destroyed in the ongoing civil war, have shapened Mourad‘s image worlds up until today. Another key ingredient is his great fascination and sense of responsibility for the history and narrations of his Armenian ancestors. Accordingly, the artist often employs historic sites and architectures as motifs in his paintings and drawings, reviving them and establishing a relation to the present. He says that an artist has the duty to be a contemporary witness of his society.

Kevork Mourad • On the Banks of the Euphrates. 2016 • Acrylic on canvas. 122 x 121,5 cm

This explains why Mourad‘s large-size painting On the Banks of Euphrates (2016) does not show a paradisiacal view of the legendary river Euphrates. Instead we are confronted with a pulsating cosmos of colors that just reveals dim forms like wings, fish scales and plants. The painting seems to burst with motion; strong splatters of paint, wiped lines, vibrant red, black, yellow and a pastel blue sky behind it all. The biblical river, whose banks were once said to be the site of Garden of Eden, marks today‘s Syrian front line between the USA and Russia and is one of the reasons of the conflict for essential water supply between Syria, Iraq and Turkey. Today this river seems to be everything but a paradise on earth. In line with that Mourad‘s painting does not only show the banks of the Euphrates as a devastated war zone, it also calls reminiscence of the historic sites and the natural environment that this river landscape first and foremost is.

With his landscape format painting The Book (2013) Mourad sharply criticizes the sole claim for validity that religions make “without considering that we are all connected as one family.“[4] Piles of dark red human bodies are scattered on the ground. Faces covered, blind, deaf and lifeless, hands and feet sprawled out, skin and clothes decorated with soft ornaments. One of the figures in the lower margin holds a book in its hands. In this work the artist also uses pastose layers of paint from which he gradually works out single forms and details. Especially for the dark contours he has developed his very own technique: Mourad presses the respective color right onto the canvas by means of a kind of pipette and then carefully wipes the viscous line. The contour, both strong and subtle, calls reminiscence of Arabic calligraphy which often goes hand in hand with traditional ornamentation.

The artist‘s calligraphic lines make an even stronger appearance in the work Facing the Sky (2014) in which a spiral of five female figures makes for the image‘s upper margin, some of them holding children in their arms, crying and moanfully stretching their hands towards the sky. This work is characterized by the pain and sorrow the women feel over the loss of their children and families. The artist explains that their lasting grief petrifies the figures to a point that they turn to stone and become part of the landscape. The feeling of grief and despair, which several of his works are characterized by – perhaps also a kind of helplessness and forsakenness in the face of current political events – is also what the painter, sculptor and poet Semaan Khawam from Beirut is occupied with in his paintings. He was also born in Syria, however, his answer to the question “Where are you from?“ is a completely different story.

Semaan Khawam (*1974) was born in Damascus and he also has Armenian ancestors. His family moved to Beirut when he was 14 years old and in 1994 they received Lebanese citizenship. However, a year before that something happened which would change everything: Khawam had just reached legal age and was drafted into military service by the Syrian Army. When he realized that he would have to return to Syria the young man panicked and tried to flee. In his attempt to escape he stepped on a land mine. Even though he lost a leg he won freedom, as he sees it today. That same year the autodidact began to make drawings, a little later he made first pieces of writing. Today the artist still lives in Beirut, even though he reaches his limits in the city from time to time. In 2012 he faced a prison sentence or a high fine for spraying a wall with a graffiti in form of an armed soldier in memory of the Lebanese Civil war. In 2014 he was beaten up by unknown persons on the street when they saw his passport and realized that he was born in Syria. Beirut drowns in piles of rubbish and generally is a mirror image of a country riven by conflicts.

Semaan Khawam • Isolation. 2017 • Oil on canvas. 149,5 x 99,5 cm

The figure of the “birdman“ is at the center of Khawam‘s artistic creation. It is the artist‘s unresting alter ego, the reflection of his feelings and inner conflicts on the canvas, torn, sad and at times angry. The observer looks right into the sad, bearded face of the Birdman (2016) in front of an ocher background. The apparition of a black bird with small eyes that glow in a threatening manner hovers above his head with curly hair. Streaks of color tears run across the portrayed person‘s cheeks. All hope seems to have gone lost here. The situation in the painting Isolation (2017) is even more forlorn and nightmarish. It shows a small wooden chest with a bowl on its surface of black and white tiles. A head of a man with a big black bird on it is in the bowl. The bird silently looks at the human head, his chest – similarly, as in the aforementioned picture – is marked with a blood-red cross. The reference to the art-historically relevant depictions of John the Baptist is obvious and alludes to great injustice and human cruelty in the face of which one can feel nothing but consternation. The work The fall of Icarus (2017) appears a little less gloomy: a figure hovers above the interior of a bright room. Its legs, rendered in different colors are spread out horizontally, it is holding a white lily in its right and a perpendicular in its left hand. The perpendicular, in return, is mounted above a small table with a pomegranate and a small sculpture on it. According to Khawam, the idea of finding inner balance and not getting to close to the sun like Icarus is the core issue of this work. The work The fall of Icarus 2 (2017), however, shows that the help of others is sometimes necessary for this task. The figure no longer hovers or falls in an interior space but in the open landscape. Its eyes are closed and another figure, standing upside down in the upper margin, holds its right hand. They seem to float in the landscape like in a dream. The question whether it is father and son – like it is the case with Daedalus and Icarus – remains unanswered.

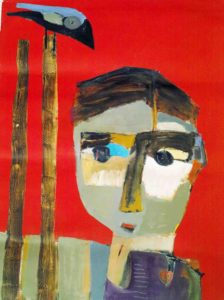

Semaan Khawam • Birdman (massacre in Syria). 2017 • Oil on canvas. 75 x 56,5 cm

The fact that not every depiction of the “birdman“ must be understood as a self-portrait is illustrated in the work Birdman (massacre in Syria) from 2017. We see the figure of a boy or a young man standing next to two wood pegs with a small black-blue bird on it in front of a lurid red background. Absorbed in thought the young man looks down, face and body separated into fields of different colors, they are split into fragments held together only by their outer margin. The answer to the question whether the young man is Semaan Khawam‘s younger self or someone else is up to the observer, as the birdman no longer is the epitomization of just one individual: “I never felt home, so as long as I am searching for a place where I truly belong, I will keep on painting birdman. This ‘birdman’ is now a symbol for all the refugees who are homesick and on the move.“[5]

The quest for our roots and identity does not only lead us into the past, as it also brings us home to the present. Our origin is just one part of us. The way we create the other part is in our hands and that’s the part that is not predetermined. It’s the part that – with a little bit of luck and courage – gives us wings to do the things that will shape the path we pursue. And the wings of Kevork Mourad and Semaan Khawam have grown very large. An extraordinary artistic gift and the bravery to express a strong position that does not only reflect reality but also questions it, is what these two very different artist personalities have in common. And despite all the agony that their works display, both artists are also characterized by a fundamental idea of hope, because Semaan Khawam wouldn‘t be the ‘birdman‘ if he did not rely on the inspiring forces of his art and the fact that it offers relief from the burdens of life: “Each time I paint, I know I am little bit healed.“[6] And when observing Kevork Mourad‘s Sumerian God from former Mesopotamia (The Sumerian Sky God, 2015) in all its splendor one thing falls into place: Sometimes it’s our roots that give us wings.

German text: Claudia Heidebluth

translation: André Liebhold

[1] Interview with Christiane Waked, September 2017 (http://www.neweasternpolitics.com/the-one-legged-birdman-syrian-lebanese-artist-semaan-khawam-journey-to-freedom-interview/, as of 05/2018)

[2] Interview with Kevork Mourad in May 2018

[3] Interview in: Amykarine Magazin 2016 (www.artfashionmag.com/kevork_mourad/, as of May 2018)

[4] Interview with Kevork Mourad in May 2018

[5] Interview with Christiane Waked, September 2017

[6] Ibd.

Interviews with Kevork Mourad & Semaan Khawam

videos: Diana Vishnevskaya & Igor Zwetkow