„Art is rather more a matter of the consciousness in our minds than any objective commitment which can change in the course of the centuries.“

(Manfred de la Motte: Preface to exhibition: Scriptural Painting. Berlin: Haus am Waldsee. 1962.)

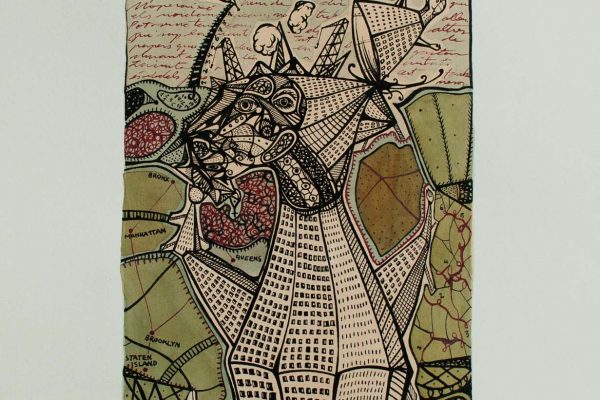

The original meaning of the Greek Word metropolis is „mother city“. Carving is the cutting of or into a material to form a figure or design.

Most people associate the word „metropolis“ with a large, important city and perhaps also with Fritz Lang’s expressionist film „Metropolis“. For some, however, the title of the exhibition „Eduard Bigas: Carving Metropolis“ will provoke the slightly subversive question as to whether the artist is engraving himself into the metropolis with his works of art or whether the mother city is being engraved into him. Who is shaping whom? If both possibilities apply, what will become visible and how?

Eduard Bigas was born in Palafrugell, a small Catalonion town at the foot of the Pyrenees in the comarque of Baix Empordà in the province of Catalonia. The name first appeared in the annals in AD 988, so it is not an ancient Greek mother city (sending out settlers to found new towns) or a present-day metropolis. Northern and Middle Europeans are fascinated by the high-lying botanic gardens of Cap Roig with Mediterranean plants, often bizarrely shaped, and by a view stretching far across the dark sea to the white-blue horizon.

But the little boy with the big blue eyes was much more impressed by his father, a surrealist and mechanic by profession, than by any botanic garden – „My father is a surrealist – not a painter but a mechanic“ – that goes well together.

„My life is my movie“, he says. We are the audience and, in general as such, we see the cinema version of a film, not the actual director’s cut with his subsequent changes to the rough or even final cut. This Exhibition (Carving Metropolis) at the Galerie Kuchling in March 2013, showing parts of Bigas’ work in the form of pictures and picture sequences could well represent an edited cut of his lifefilm.

The earliest works shown here at this exhibition came into being during a three-month sojourn in Australia. It is no longer the Mediterranen but the Pacific that governs his work – „so free, never dark“. He employs natural tones and blue – no sketches. Even later Eduard Bigas will never make use of sketches. His paper is delicately dyed with tea, he applies water colours and employs the surrealistic method of écriture automatique or automatic writing. For the first time, forgoing any clarification as to their meaning or power of communication, letters are penned to create forms: harmony, balance, beauty.

Following his stay in Australia he proceeds to New York for two months. This is the metropolis he starts out with and we no longer see wide blue spaces but, instead, towering masses of stone that cannot be depicted in gentle tones. Edgar Bigas now employs other colours. „Not blue, but green and black.“ Nevertheless, he continues to dye his paper with tea. The drawing pen becomes a carving knife: hence „Carving Metropolis“. The same technique applies equally to the carving knife and the drawing pen: once applied to the paper, it may only move in one direction. There can be no to and fro, backwards and forwards as with a brush. However, the pen can be re-applied, thus deepening the cut or the line.

And „Black stops being a colour to convert itself into the skin or contour of all shape or space, whether it be in the form of line, stain or letter.“ „Black ink lasts forever.“ Just as if tattooed. Something else also occurs: not only does the writing, but also the lines drawn to form the frame and shape and which are filled in to obtain their significance, appear „automatic“. An environment is associated around the frame and a legend is being narrated.

In New York Bigas also produces portraits of homeless people and jazz musicians amongst others, whereby he continues to use paper dyed with tea and draws with black ink. His respect for his subjects and his curiosity do not permit him any associations of his own, but require him to efface his own ego and in this withdrawal do justice to the others and thus be able to capture the aura of his vis-à-vis.

„Life is like a marathon: you have to go on.“ He moves to London. „London and New York are not so much different“ – figures Eduard Bigas. This is his next metropolis and it is here that he will spend the next ten years of his life.

„The good things I keep going on“. He also starts out on a new venture and begins to paint in oil and acrylic. Just as he used the subtle technique of using tea to dye his paper, he also uses the base as an integral part of his portraits. The structure of the canvas, which he hides and employs as a vital component of his oeuvre, seems to vanish. In some parts the impression is given that the first coating of the paint is worn or rubbed off, or the various base coats seem not to have been completely painted over but integrated into the motif.This makes his pictures glow, and it becomes more and more apparent that Eduard Bigas, no matter whether he is using paper or canvas, does not simply want his art to portray but also to gleam and glow. The black lines hold and embrace thoughts, dreams and phantasies, which though intangible and ever so transient by nature, then determine the form and course of the lines. But they in turn are captured by the lines and written into the oeuvre. This has been done intentionally and the status quo thus achieved affords no escape or alteration. The lines are liberated in the mind of the viewer whose associations and interpretations allow them to be filled with new life.

London proves tough. „All the city collapses because of money.“ But: „The prize is ok to survive any city.“ As in most movies, love also plays one of the leading roles in his lifefilm, but sadly this does not always necessarily culminate in a happy ending.

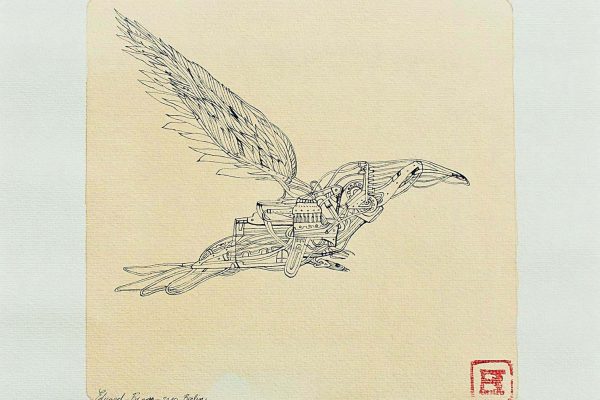

After ten years he leaves London and heads for Berlin. „Berlin is always moving.“ At the beginning of his sojourn he chooses a restful, in all senses resting place – the so-called Spinn[1] Mausoleum in the Friedrichswerderscher Cemetery in Bergmann Street. The empty neo-Gothic chapel there is flooded with light. Bigas listens to Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 „Resurrection“ and the words of the Fifth Movement: „What was created/Must perish/What perished, rise again!/ Cease from trembling!/Prepare yourself to live!“ (From the poem „Resurrection“ by F.G. Klopstock) For the record, a Catalonian in a neo-Gothic chapel in a Prussian cemetery carves mit a pen the dream of his resurrection. Outside Berlin crows are hopping and croaking; there are none of the proverbial capricious Spanish bats – or maybe there are! After all, we have them, too. They are a native species.

„You need to believe.“ „You need time.“ Thus resurrected, he has truly arrived in Berlin – yet another metropolis, a fleeting Now to exert its influence on him and a Here that he depicts as a “Man of good fortune” beside a typical Berlin street lamp, perhaps even more bent by drunks than Martin Kippenberger’s canvas of a street lamp “Kellner des…” (“Waiter of …”). Or also as “Unknown man” and “Transitory presence”.

Eduard Bigas is an amiable man, who willingly provides information on his work. His sketch books and his surreal collages make it easy to relate to his origins and to what has influenced him.

He would like his work to be treated with due respect..

We have but to look to see. This enables us to find for ourselves the answers to the questions we posed at the beginning.

Bigas uses a red stamp to sign his work.

The English-language quotations in inverted commas are taken from interviews with Eduard Bigas in his studio and the Galerie Kuchling on 9. February 2013. The other quotations come from from the artist’s homepage.

(Author: Susanne Gaebler, Translation by Alexander Gunn)

[1] J.C. Spinn & Sohn. Established in 1877. Manufacture of bronze goods and objects for gas and electric lighting as well as gas burners. In 1894 the company took on AEG’s lighting department. In the main, 300 persons were employed in the factory at 9 Wasserhorst Street. During the First World War the production of the company’s peace time products came almost entirely to a stillstand, but the factory was operating to capacity with orders from the army so that the deficits carried forward in the final year of the war could be amortized completely. The publicly traded company in Berlin was able to pay appreciable dividends of 10-16%, however reverting to the production of civil goods after the First World War proved extremely difficult. The manufacture of craft products became more and more unprofitable and had to be scaled back. The company branched out into other areas of which the cinema department was the only new branch that showed a relatively good development. Thus weakened, the company, which was renamed “AG. Vorm. J.C. Spinn & Sohn” in 1918, finally declared bankruptcy in 1928. (Information from Berlin Address Book 1875-1899 and various Wikipedia articles.)

Exhibition from 9. MÄRZ 2013 – 9. APRIL 2013

ARTIST