Eduard Bigas – Time and the Others

27th September – 25th October 2019

A certain morning, when waking up, I slowly opened my eyes welcoming the light that poured in. I then proceeded to look around the room ― it was a familiar room, I had missed it, so, aware of my absence, I instinctively looked for my plants. Of course, the first thing that I see every morning are my plants, besides, they are young, still developing and I worry about them. As I inspect carefully on the only living beings in my room besides me, I remember Bigas’s paintings. I remember the leaves, dark green and purple drooping like hot wax; the stems, entwined, some sprouting upwards; the flowers, with their complex reproductive systems.

Then I notice how the light hits them, a light that cuts through but also bounces back, how they seem to vibrate, germinate with the presence of the light.

It is an inescapable feeling, that of standing in the presence of nature. Imagine a luxurious forest, steaming with life, vegetation, animals. We cannot but feel pleasure and wonder, and also a certain sense of security. I wonder… how did Bigas’s paintings provoke such feelings in me? I thought, were they to be the last memory of the world, would they be representative of its beauty?

Eduard Bigas is, with weight and measure, methodical. He has, at the same time the wild spirit of a perpetual student, always eager to learn, to evolve. This means that he will obsess over his craft, the control of the light and the placement of the pigments. If from a distance Bigas’s paintings seem peaceful, and they do perform, in a way, as an exercise for meditation, as one moves closer, the detailed organic elements and swooshes of colour reveal a tiny biosphere incubating.

Bigas told me many times that his only deep, deep desire is that people find his paintings “beautiful, nothing more”, like a true romantic, “everything is invented” he says. There is no fear in Eduard’s perceptive eyes. “There are no answers. They don’t matter.” We can pose questions, but beauty cannot truly be explained. It must be experienced.

Like vitrines, aquariums or terrariums, the tiny ecosystems are arranged with the thoughtfulness and precision of a Japanese garden. It rests upon us to observe and appreciate. I did not meet Eduard Bigas before he travelled to Japan, but I know that being there has had a great impact on him. Like the Japanese, he draws down on the material in hopes to dominate and bare it justice. Even the textures of the background follow a careful syncopated and meditative rhythm.

They also remind me of the naturalist movement, the appreciation of nature above all things, the depiction of a physical environment, and trying to translate it into the canvas in the treatment of form, colour, space, as it might appear in nature. The pigments themselves, being preferentially derived from natural minerals, are the enactment of nature itself, and therefore can be drawn in any shape or form and will always be, well, natural.

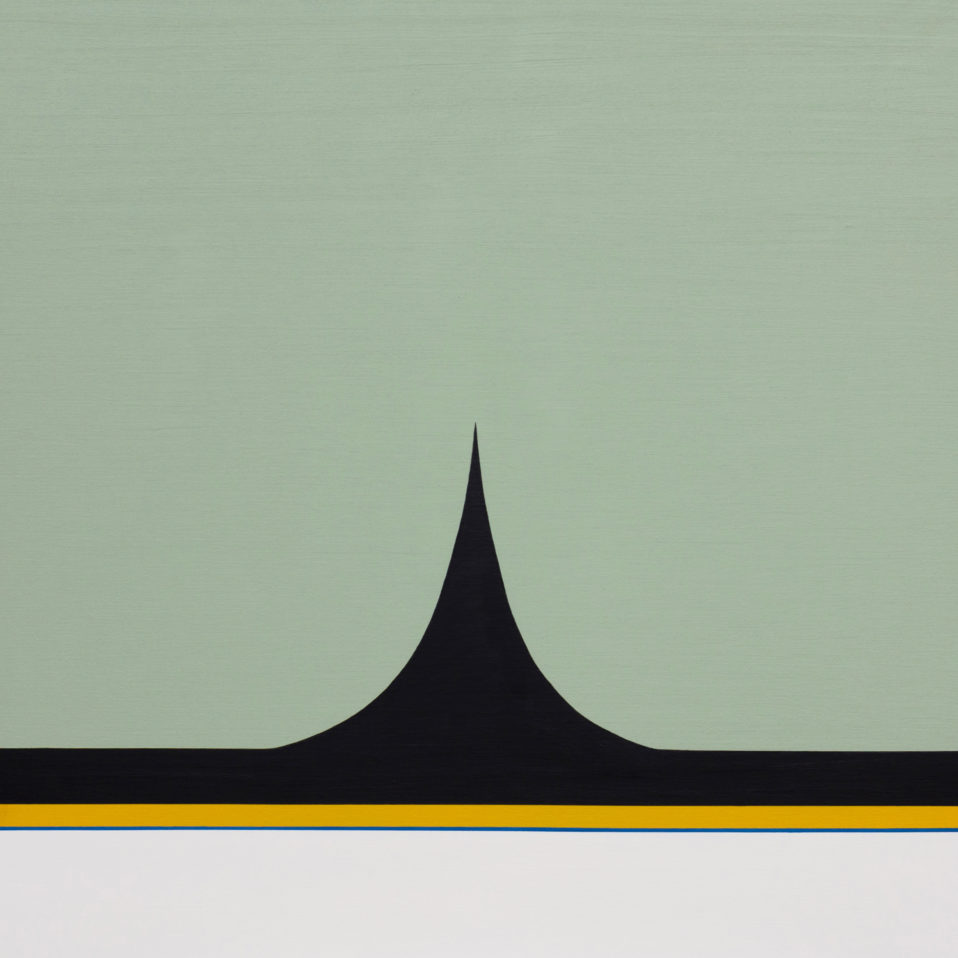

In ‘Time and the Others’ Bigas orchestrates three movements, three series, three different moments in time.

In ‘Geometry of Time’, the new “crazy” ideas and experiments, there is precision and control. The geometries determine the limits in which the colours are existing. Contained, like a closed circuit, from which they cannot escape.

In turn, ‘Time and the Others’ seizes the opportunity to let the organic shapes drift freely, and finally in ‘Transfigurative Time’ – Bigas applies the same rich, sometimes even more intricate elements, but instead of letting them live harmoniously, the reality is bluntly cut obliterating entire sections of the canvas with flat light colours. These trespass as a suggestion of a missing memory, as if something needs to remain hidden, forgotten.

Bigas manipulates the measure of time to adapt it to his comprehension. In an attempt to create and capture the beauty in its purest form, his compositions seem to bend, stretch and transfigure pigments and shapes according to Bigas’s will.

Text: C. Palma