Jarmila Mitríková and Dávid Demjanovič were born in the mid-1980s in Czechoslovakia, a land and political system that no longer exists today. And yet much has remained, which like a common red thread of past times, trails through the present of their homeland: buildings, everyday objects, memories, stories, traditions and rites, which are still today part of Slovakian culture and identity. In their works, Mitríková and Demjanovič trace these relics and work with humour and originality to create a fantastic distillate of Slovakian culture.

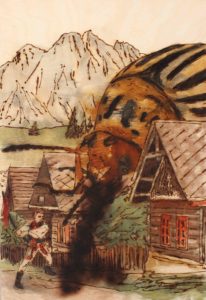

There is, for example, the propaganda campaign of the potato beetle, which is also known in Germany: at the beginning of the 1940s, a far-reaching potato beetle plague attacked innumerable crops in Nazi Germany. In the 1950s, the GDR and several eastern European countries were also afflicted by the plague. For both the Third Reich and the Eastern Block, the supposed fiend behind the six-legged gourmand was quickly identified: the Americans had dropped the beetle as a biological weapon upon the enemy. The fact that misfortunes are exploited politically is nothing new, but Mitríková und Demjanovič demonstrate how grotesque such a ‘creative’ chain of cause and effect can become in their painting Attack of American bug (2015). The normally tiny beetle is suddenly a shockingly monstrous size, its huge sensors poking between the roofs of two houses, whilst fighting against a man with a burning torch. It can only to be hoped that Gregor Samsa is not within the chitin shell, so Kafkaesque and surreal is the representation.

But the Communist system also possesses special secret weapons, as the artist duo shows in Spiritists Séance (2014): six female pioneers summon the ghost of a long dead politician to answer their carefully listed questions about the political future. The evocation of the ghost, a popular notion from the mid to the end of the 19th Century, is relocated here to the Eastern Block, where it ironically visualises the questionable foundations of the Communist system. The call of ghosts and the consultation of oracles and astrologists have historical routes, as is well known: whether it be the oracle of Delphi or Wallenstein’s personal physician and astrologist Giovanni Battista Seni. In case of doubt: it does not appear to be a disadvantage to engage with transcendental or ulterior powers.

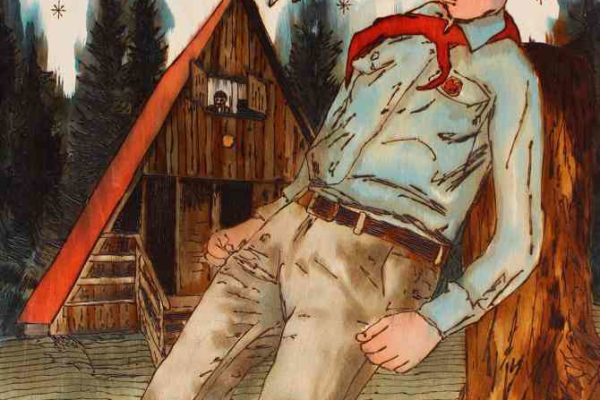

And when the gaze of the two artists caricatures the Communist past of their home country, there speaks at the same time a great fascination for their own history, which is apparent in more than just the motifs of the artwork. The technique of pyrography used by Mitríková and Demjanovič has a long tradition in Slovakia and other Eastern European countries, where children are taught this traditional craftsmanship, some of them already at school. The surface of wood is burnt with an electrically-heated pencil, which replaces the former hot iron. This creates dark, relief-like contours, which can be subsequently filled with colours. These two elementary work steps are often shared by Mitríková and Demjanovič: while Demjanovič first lightly ‘writes with fire‘ on the wood, Mitríková colours the burnt figures and shapes with wood paints, ink or wood stain. An additional ornamental element is the surface of the wood. In some works the restrained grain appears discreetly, whilst other times the lively wooden structure becomes a component of the pictorial space, as for example in Temptation (2014).

Somewhat lost in the picture space, a man in a khaki suit with drooped shoulders stands absentmindedly holding a bom-bom, or ‘waving element’, with the Czechoslovakian national colours whilst two winged black demons encircle him. The grained surface of the wood forms the background of the painting but remains visible under the colouring of the man’s figure, thus intensifying the impression of a power penetrating him from the outside. The features of the man are similar to those of the politician Alexander Dubček, who from 1968 to 1969 was the most powerful Communist politician in Czechoslovakia and the guiding figure of the Prague Spring, before he joined the anti-Communist opposition in 1989 to become one of the central figures in the so-called Velvet Revolution. In their black, shadowy form, the dazzling demons recall one of the similarly ghostly beings in Goya’s cycle of etchings Los Caprichos, in which the Spaniard, with his depictions of a terrifying world full of demons, witches, and spirits, displays his social criticism. In addition, Temptation also refers to the particular technique of pyrography and its material-specific peculiarities and expressive possibilities. The previously mentioned works Attack of American bug and Spiritist Séance, in which Mitríková and Demjanovič skilfully portray fire, soot and smoke, also refer to the technique of pyrography itself. With such self-reference and their extraordinary technique, Mitríková and Demjanovič free the art of pyrography from the stigma of naive folk art and, with imagination and a postmodern twist, assign it a special place in contemporary art.

Somewhat lost in the picture space, a man in a khaki suit with drooped shoulders stands absentmindedly holding a bom-bom, or ‘waving element’, with the Czechoslovakian national colours whilst two winged black demons encircle him. The grained surface of the wood forms the background of the painting but remains visible under the colouring of the man’s figure, thus intensifying the impression of a power penetrating him from the outside. The features of the man are similar to those of the politician Alexander Dubček, who from 1968 to 1969 was the most powerful Communist politician in Czechoslovakia and the guiding figure of the Prague Spring, before he joined the anti-Communist opposition in 1989 to become one of the central figures in the so-called Velvet Revolution. In their black, shadowy form, the dazzling demons recall one of the similarly ghostly beings in Goya’s cycle of etchings Los Caprichos, in which the Spaniard, with his depictions of a terrifying world full of demons, witches, and spirits, displays his social criticism. In addition, Temptation also refers to the particular technique of pyrography and its material-specific peculiarities and expressive possibilities. The previously mentioned works Attack of American bug and Spiritist Séance, in which Mitríková and Demjanovič skilfully portray fire, soot and smoke, also refer to the technique of pyrography itself. With such self-reference and their extraordinary technique, Mitríková and Demjanovič free the art of pyrography from the stigma of naive folk art and, with imagination and a postmodern twist, assign it a special place in contemporary art.

However, the fact that the two artists are not limited solely to one material can be seen in their sculptures made of chamotte, fired clay, brick or porcelain. In Building of Morena (2015), Mitríková and Demjanovič thematise the ritual of building a life-size figure of the Slavic goddess Morena every year on 21st March, in Slovakia and other Eastern European countries. To celebrate the end of the winter, the figure of the goddess is burned or thrown into water following a procession. The coloured, granular surface of the sculpture gives the depicted scene something both sacred and morbid. If one also becomes aware of the burning process that the figure has already passed through, then the sculpture reveals the essence of the joyous festival: an uncanny myth that recalls the burning of witches and water-testing (whether she floats or sinks). In Guardians of national spirituality (2013), the interlacing of religion, custom, and culture is intensified in the representation of parallel periods: whilst young girls dance in a circle in Slovakian costume dresses and are conjured up by a masked priest with a Byzantine double cross (which is at the same time the coat of arms of Slovakia) the viewer sees in the background the silhouette of a glassy geodesic dome that sits like an UFO in the Slovakian forest landscape. When Mitríková and Demjanovič juxtapose the spiritual past, the present and the future of their homeland, they appoint themselves, despite all their irony, as guardians of their own cultural identity and, if you will, national identity. This, of course, cannot be exactly the same for everybody, for it is instead the individual weave of facts, memories, narratives, customs, rituals, socialization and their own experiences and perceptions. And how thrilling and amusing a dash of magic, a sparkle of superstition and a portion of narrative freedom can be in this complex, and often so serious, weave, as the works of Jarmila Mitríková und Dávid Demjanovič show us.

However, the fact that the two artists are not limited solely to one material can be seen in their sculptures made of chamotte, fired clay, brick or porcelain. In Building of Morena (2015), Mitríková and Demjanovič thematise the ritual of building a life-size figure of the Slavic goddess Morena every year on 21st March, in Slovakia and other Eastern European countries. To celebrate the end of the winter, the figure of the goddess is burned or thrown into water following a procession. The coloured, granular surface of the sculpture gives the depicted scene something both sacred and morbid. If one also becomes aware of the burning process that the figure has already passed through, then the sculpture reveals the essence of the joyous festival: an uncanny myth that recalls the burning of witches and water-testing (whether she floats or sinks). In Guardians of national spirituality (2013), the interlacing of religion, custom, and culture is intensified in the representation of parallel periods: whilst young girls dance in a circle in Slovakian costume dresses and are conjured up by a masked priest with a Byzantine double cross (which is at the same time the coat of arms of Slovakia) the viewer sees in the background the silhouette of a glassy geodesic dome that sits like an UFO in the Slovakian forest landscape. When Mitríková and Demjanovič juxtapose the spiritual past, the present and the future of their homeland, they appoint themselves, despite all their irony, as guardians of their own cultural identity and, if you will, national identity. This, of course, cannot be exactly the same for everybody, for it is instead the individual weave of facts, memories, narratives, customs, rituals, socialization and their own experiences and perceptions. And how thrilling and amusing a dash of magic, a sparkle of superstition and a portion of narrative freedom can be in this complex, and often so serious, weave, as the works of Jarmila Mitríková und Dávid Demjanovič show us.