The unknown, the foreign, the strange – all are abstract ideas rife with abysmal depths. Far too easily do we tend to abuse them as projection screens for our own fears and desires, while merely speculative causal chains deliver proof of the bounds of our knowledge. There are many present-day examples of this phenomenon, however, European art history also offers a vast pool of motifs. The harem in the Ottoman Empire presumably is the one subject that is most impressively associated with stereotypes of the foreign and exotic. The European concept of the Orient has been coined by Western harem depictions since the 16th century, always following the high “standard of visualizing the most inaccessible aspect of Islamic culture.“[1] Over the time the motif of the harem became a platform for the most diverse discourses. While French 16th century costume illustrations documented the harem members‘ social functions and cultural affiliations on basis of their attire, skin colour and gender, the Odalisque motifs by Ingres from around three hundred years later focus on the representation of a classic ideal of beauty in an Oriental context. By the mid 19th century the development of the subject in European painting saw a clear “reduction of the harem’s iconography to stereotypes, for instance in paintings by (Jean-Léon) Gérôme. Orientals are now reduced to eroticism, idleness and violence.“[2] Matisse eventually made his oriental-erotic fantasies subject to a superordinate ornamental formal principle.

These examples demonstrate how much European artists, often with little to no knowledge of the Orient, coined the idea of the harem, especially during the heyday of European colonialism.[3] The harem as the epitome of sexual excesses and male violence on the one hand and, on the other hand, the reality of an upper-class phenomenon, a strictly hierarchic structure that was home to the sultan‘s wives, their children, other female family members, servants and eunuchs and which, at least for the wives and the sultan‘s mother, offered relatively big power potential and educational opportunities.

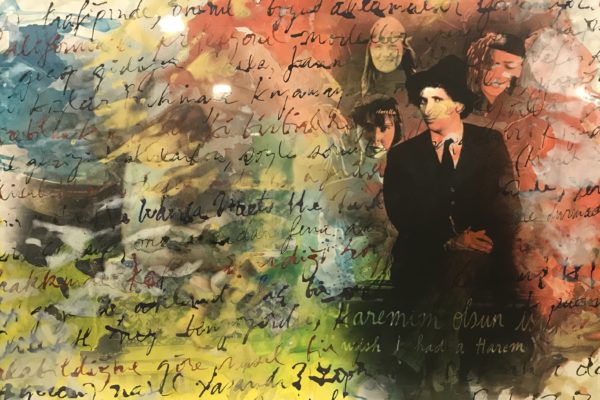

The current exhibition I wish I had a harem of the Turkish artist Bedri Baykam (*1957) helps us to overcome the art-historically anchored Eurocentric view of the harem and the Orient in general, at the same time he broadens our perspective and increases our awareness through ironic twists. In his so-called 4D-work, a complex lenticular print titled Harem d’Avignon is 100 years old (2007), Baykam self-confidently places a photograph of his younger self between two portraits of Pablo Picasso, while a mirror-inverted detail from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which changes with the observer‘s position, hovers in the upper right margin. Cut-out photos of women, some of them inscribed with names, can be found in the picture‘s left half as well as all over the image area. The work is inscribed with the caption: “Bir Haremim olsun isterdim (I wish I had a Harem).“ This remarkable work is not only a reference to Picasso‘s Cubist masterpiece but also to Baykam‘s own work, as the self-portrait and the photos of women come from a collage he had made as early as in 1987 and for which Baykam‘s ironically devised dream was eponymous. Today the work is in possession of Istanbul Modern. By analogy, Baykam opposes himself and his art to Picasso and his oeuvre in this work. In a subtle manner he combines motifs from both pictorial worlds through the harem context. Eventually, Picasso’s brothel scene is turned into a harem depiction. Suddenly the following questions arise: Who’s talking? Who wishes for a harem? Baykam or Picasso? And what’s the impact of the context on the message of Picasso’s famous motif? Baykam answers the latter as follows: “So when I think of Picasso’s Demoiselle d’Avignon, that painting also looks like a scene from the Harem, although from a very different world including Africa. But also let’s not forget that Picasso had looked in depth to the French Orientalist painters and the harem subject as well.“

To Bedri Baykam, former wunderkind and vehement fighter for democracy in his home country, Picasso’s oeuvre has crucial influence on his art. He is most fascinated by the Demoiselles motif, which he uses on many occasions. In Demoiselles (2009), a 4D work in rather dark tones, he renders the ladies’ striking arm postures in neo-expressionistic manner and correlates it with a portrait of the young Picasso, with a self-portrait titled ”Toni“, with two erotic photographs of women and with several pieces from Cézanne’s The Bathers, which become visible, depending on the observer’s perspective, at the bottom of the picture. In the large-size painting Demoiselles and the Sailors (2014), executed in strong colours and expressive brush-strokes, Baykam reinterprets a preliminary study for the work. What is particularly interesting about it are the elements the artist inserted into the original motif: The dark male figure in left, for instance, wears a sort of cowboy hat, additionally, Baykam integrated three different textiles in the upper margin. On the one hand, the artist skilfully weaves different cultural elements into the famous work, on the other hand, he plays with the surface’s optical and haptic properties, thus adding a spatial dimension. In the large-size lenticular print Harem Now and Then – 2 (2008) Baykam is occupied with another artist of early Modernism: By placing photographs of Rodin’s sculptures and various motifs of bathers and nudes in front of a historic view of Istanbul, he creates a provocative erotic-historic combination of East West, of art- and cultural history and present age. One thing is for sure: Many of Baykam’s works can only be unscrambled with respective knowledge of art history, which is, just as it is the case with Baykam’s artistic roots, based on European Modernism. “The nicest influence is Picasso for sure, of course …“, says Baykam. “What is important for me about is the fact that he has had so many different periods and styles without becoming a prisoner of any of them… The capacity of change or self-disguise is also present in Piabia. I loved Van Gogh’s brush-stroke or Tapies’s spontaneity as well as the journey of Jackson Pollock starting with cubism and surrealism and working its way up to his drip works.“ As we see, Baykam is not shy of using motifs from all these sources of inspiration in his works – well, he downright loves it! By combining them with various historical and contemporary pictorial elements he attains an inimitable visual conception somewhere between collage, painting and spatiality. The complex web he courageously weaves between Orient and Occident is more than overdue – as, for Baykam, it is best exemplified by the motif of the harems: “The French Orientalist painters, mainly Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Leon Gerome, depicted the harems as well as the Turkish hamam (bath) in some beautiful scenes … My first painting dealing with that subject was entitled ‘Ingres-Gerome this is my Bath‘ at the Istanbul Biennial (1987). It was a reaction to the West, all about my theories regarding Eastern and Western art … In short I was saying to the West: ”Stop using all our iconographies and believing that you transfer the ’copyright‘ to yourselves after you have transferred them. Stop making us feel strangers in our own backyard, as you have always done since the beginning of Modernism“.

Baykam, born in Ankara and active in Istanbul, does not want his art to be reduced to his origin, instead he scrutinizes art-historic visual habits and their contexts, freely chooses his sources of inspiration and vehemently claims his spot on the time-line of art history, which obviously is not a linear one. If necessary, he even uses a Readymade in form of an empty frame freely suspended in the show room in order to once more pose the question: What do we see when we see art? Perhaps: Ourselves! Ourselves in context of an artistic idea, ourselves and our mutability in space, time and context. We see an encounter of the familiar and the strange.

Baykam, born in Ankara and active in Istanbul, does not want his art to be reduced to his origin, instead he scrutinizes art-historic visual habits and their contexts, freely chooses his sources of inspiration and vehemently claims his spot on the time-line of art history, which obviously is not a linear one. If necessary, he even uses a Readymade in form of an empty frame freely suspended in the show room in order to once more pose the question: What do we see when we see art? Perhaps: Ourselves! Ourselves in context of an artistic idea, ourselves and our mutability in space, time and context. We see an encounter of the familiar and the strange.

[1] Silke Förschler: Bilder des Harem. Medienwandel und kultureller Austausch. Cologne 2010, p. 296

[2] Silke Förschler 2010, p. 298

[3] Fundamental work on Orientalism is the study “Orientalism“(1978) by Edward Said, which is, however, also quite controversial.

text: Claudia Heidebluth, translation: André Liebhold

Interview with Bedri Baykam